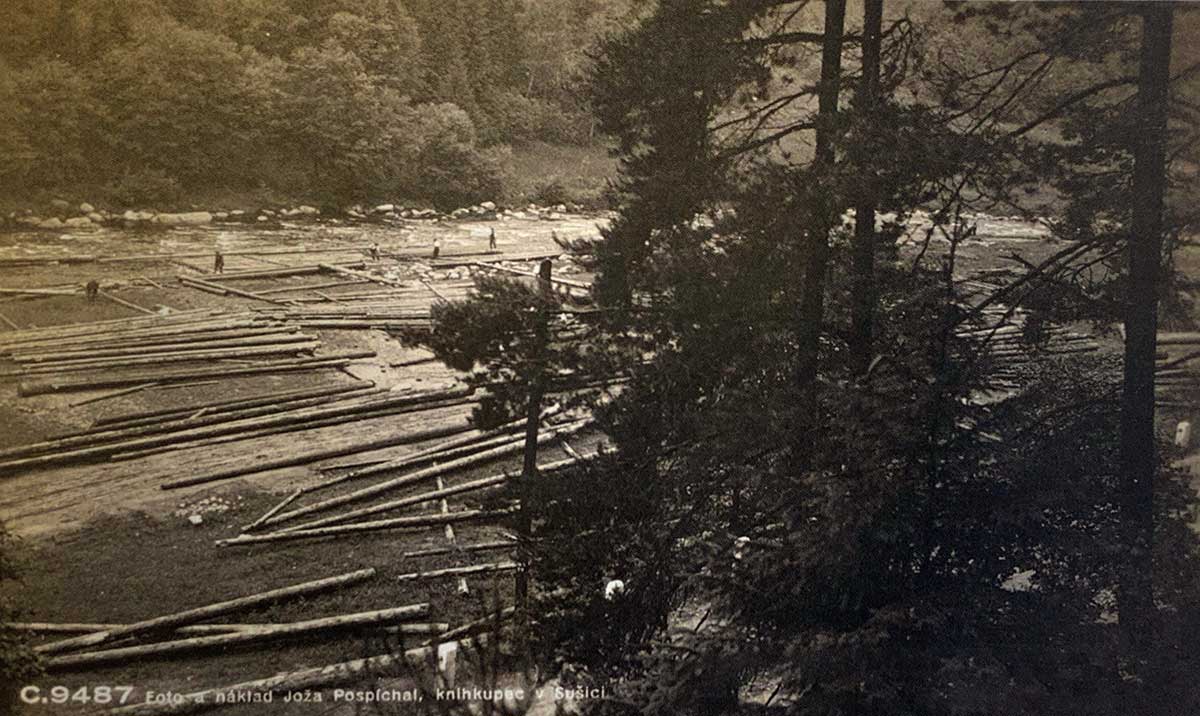

9 – Paula’s Meadow Raft Tying Station

Paula’s meadow served as a raft tying station. The stations were specially modified areas on the bank of the river, often close to weirs, where timber logs would be tied together with withe into raft, which were then sent down the river. Often there was a wooden shelter or box, in which the rafters stored their equipment or themselves hid from bad weather.

Apart from typical tying stations such as Paula’s meadow, there were also the so-called “slides” along the bank – those were tying stations which were not close to the river’s surface but higher up and the logs were slid down the sloped bank to the river via either a natural ravine or specially made wooden through. If the spot was narrow logs were sent down headfirst, if it was wide enough, they were rolled down.

Apart from typical tying stations such as Paula’s meadow, there were also the so-called “slides” along the bank – those were tying stations which were not close to the river’s surface but higher up and the logs were slid down the sloped bank to the river via either a natural ravine or specially made wooden through. If the spot was narrow logs were sent down headfirst, if it was wide enough, they were rolled down.

By some moorings or rafters’ inns (the most famous one in Šumava being Myší Domky (Mice Houses) by Rejštejn), where rafts had to stop, were moorings called “tents”. Rafts were tied with withe or wire to an iron circle with a diameter of 14–20 centimetres, which was then reeved through a hole in a stone and poured over with lead. Stone blocks with an edge of around 60 centimetres were then sunk into the ground.

The rafters would dress the same as forest labourers – their trousers were made out of solid rough fabric to protect from abrasion, shirts were made out of a slightly lighter fabric. They wore vests or coats to protect themselves from cold. It was their footwear which differentiated them from forest workers – they wore high leather boots with buckles which allowed for easy putting on. Apart from the strength of the material they were made out of, additional layer of protection was provided by grease, fish oil, or fat. These special boots which they had to have made specially were later on replaced by cheaper and more practical rubber boots.

The rafters usually went through the whole process of rafting, from the very cutting down of the tree to its delivery to Prague. They used various tools, which were not really needed during the rafting itself. In the forest it was essentially two different kinds of saws. A two man cross cut saw was one. Its wide steel blade cut in both directions. Men held it by wooden handles and it was used primarily for logging. A smaller saw was only wielded by one man. Its wooden arch was often made by the rafters themselves from a steamed a bent branch. This saw was used to cut any wood that was smaller in diameter directly on the tying stations and it was also needed during the journey. The logs had to be peeled so a peeler was needed as well.

Due to the inaccessibility of other methods, the rafters used measuring devices which they made themselves. Larger things were measured using a so-called measure, which was a lath of four to six meters with a mark on each meter. It was used to measure logs. Considering its length, more than one man were needed to wield it and so a more practical tool was used – it was made out of laths fixed together to create a letter A shape with nails at the end of each, exactly one meter apart. This allowed one person to measure lengths easily.

To manipulate longs in the forest and at the tying station, a curved iron tool called turner was used. On its end it had a curved tooth with which it cut into the wood. To manipulate the logs while rafting, a hook with a slightly misaligned spike was used. Another was then used to pull them out of the water.

Axes were used to further process the wood. A slightly more expensive one and not used by all rafters was used to cut ores. A very specific type meant specifically for the rafters was a thin axe with a long thin beak-like curved blade. It was used to make holes in the end of logs through which a thin log was inserted to hold the raft together. Another tool with a strong spiral point was needed to drill openings in logs. The point was often covered by a wooden sheath which the rafters made themselves from soft wood, or it was wrapped in a cloth or a piece of paper. Each string of rafts was marked with the name of a company. Usually it was written on a sail on the second raft. Apart from the timber owner’s name there was also the name of the gatekeeper – the rafter leading the whole string of rafts. It could not just be anybody, a gatekeeper needed a special patent which he used to prove his identity. To receive this patent, one had to pass an exam in Prague to prove he was capable of the task. Rafts were tied together so the final length of the whole sting could be up to 150 meters.

The rafters would dress the same as forest labourers – their trousers were made out of solid rough fabric to protect from abrasion, shirts were made out of a slightly lighter fabric. They wore vests or coats to protect themselves from cold. It was their footwear which differentiated them from forest workers – they wore high leather boots with buckles which allowed for easy putting on. Apart from the strength of the material they were made out of, additional layer of protection was provided by grease, fish oil, or fat. These special boots which they had to have made specially were later on replaced by cheaper and more practical rubber boots.

The rafters usually went through the whole process of rafting, from the very cutting down of the tree to its delivery to Prague. They used various tools, which were not really needed during the rafting itself. In the forest it was essentially two different kinds of saws. A two man cross cut saw was one. Its wide steel blade cut in both directions. Men held it by wooden handles and it was used primarily for logging. A smaller saw was only wielded by one man. Its wooden arch was often made by the rafters themselves from a steamed a bent branch. This saw was used to cut any wood that was smaller in diameter directly on the tying stations and it was also needed during the journey. The logs had to be peeled so a peeler was needed as well.

Due to the inaccessibility of other methods, the rafters used measuring devices which they made themselves. Larger things were measured using a so-called measure, which was a lath of four to six meters with a mark on each meter. It was used to measure logs. Considering its length, more than one man were needed to wield it and so a more practical tool was used – it was made out of laths fixed together to create a letter A shape with nails at the end of each, exactly one meter apart. This allowed one person to measure lengths easily.

To manipulate longs in the forest and at the tying station, a curved iron tool called turner was used. On its end it had a curved tooth with which it cut into the wood. To manipulate the logs while rafting, a hook with a slightly misaligned spike was used. Another was then used to pull them out of the water.

Axes were used to further process the wood. A slightly more expensive one and not used by all rafters was used to cut ores. A very specific type meant specifically for the rafters was a thin axe with a long thin beak-like curved blade. It was used to make holes in the end of logs through which a thin log was inserted to hold the raft together. Another tool with a strong spiral point was needed to drill openings in logs. The point was often covered by a wooden sheath which the rafters made themselves from soft wood, or it was wrapped in a cloth or a piece of paper. Each string of rafts was marked with the name of a company. Usually it was written on a sail on the second raft. Apart from the timber owner’s name there was also the name of the gatekeeper – the rafter leading the whole string of rafts. It could not just be anybody, a gatekeeper needed a special patent which he used to prove his identity. To receive this patent, one had to pass an exam in Prague to prove he was capable of the task. Rafts were tied together so the final length of the whole sting could be up to 150 meters.